Already in the Middle Ages there were laws that assigned responsibilities for poor people, within families as well as for the local community.

Kristiansand was founded in 1641, and poverty was a serious social problem from the outset. The Town Privileges of 1643 enforced the installment of an administrator of poor relief.

In 1672, the number of poor people had grown to the extent that the King imposed new measures to address the problem. Among them was the decree that the churches of Agder should make collection plates to be used when collecting alms for the poor.

In 1683, betleri, begging, had grown into a problem of such magnitude that the authorities tried to separate those truly in need from those who could work, but did not want to.

In 1722 the first lemmer, paupers, were taken into the hospitals. Fattiglemmer was the contemporary name for poor people on welfare. This meant that the hospitals were partly used as poor houses.

The sheriff of Oddernes, Tveit and Vennesla established a register of poor people in 1730, listing 17 in Oddernes, 5 in Tveit and 14 in Vennesla. Of these 36 people, 28 were women, and 19 older women.

In 1734, Kristiansand was afflicted by a great fire. Half of the town’s 640 houses burnt down, and many families lost all their belongings. The number of poor people increased dramatically.

Many townspeople died of contagious diseases in 1741, as a direct consequence of poverty and starvation.

In 1753, Bishop Paludan said that he had never seen as many paupers and beggars in any other place than in Kristiansand. In many places in Agder, such as Audnedal, Mandal and eventually Oddernes, priests called for for farmers to contribute a share of their own corn or other goods.

Through the years, many individuals have attempted to organize aid for the poor. Among the most significant was the diocese’s District Governor Adeler and Bishop Hagerup in Kristiansand. In 1782, they developed a system to handle registration and poor relief, as well as punishment for the idle people and beggars.

In 1786, a poor relief authority was established in Agder. The old, the physically and mentally ill, orphans, prisoners and alcoholics, qualified to obtain poor relief. Begging was now explicitly forbidden. Poor people were continuously registered and assisted. Administrators assessed who was in need of support, and what kind of support they would need.

At the beginning of the 19th century, poorhouses and work houses were established.

In 1803, Kristiansand’s poor people’s fund provided relief for 190 individuals, and this figure grew to 700 in 1831 and 1000 in 1855. The fund’s expenses were great, and poor relief was the public issue that most people cared about. Begging was still widespread. Private individuals as well as organizations contributed with funds to improve living conditions for different groups of poor people.

The first poor law appeared in 1845, dividing the poor into three groups: 1. Old and sick who were unable to provide for themselves. 2. Children who did not have parents who could take care of them. 3. People who could provide for themselves, but not sufficiently. Begging was still subject to severe penalties.

10, 8% of all inhabitants in Kristiansand received support from the Poor (fattigvesendet) in 1855.

A new poor law was introduced in 1863, placing greater responsibility on relatives and employees, and the poor commission received greater powers to reject applications. Certain areas of responsibility were transferred to the municipal authorities.

A nation-wide poverty survey was performed in 1866. On average, 4,0% of Norway’s population received support from the poor people’s authority. In Kristiansand the figure was 12,3%. More than twice as many women as men received poor relief, mostly older women.

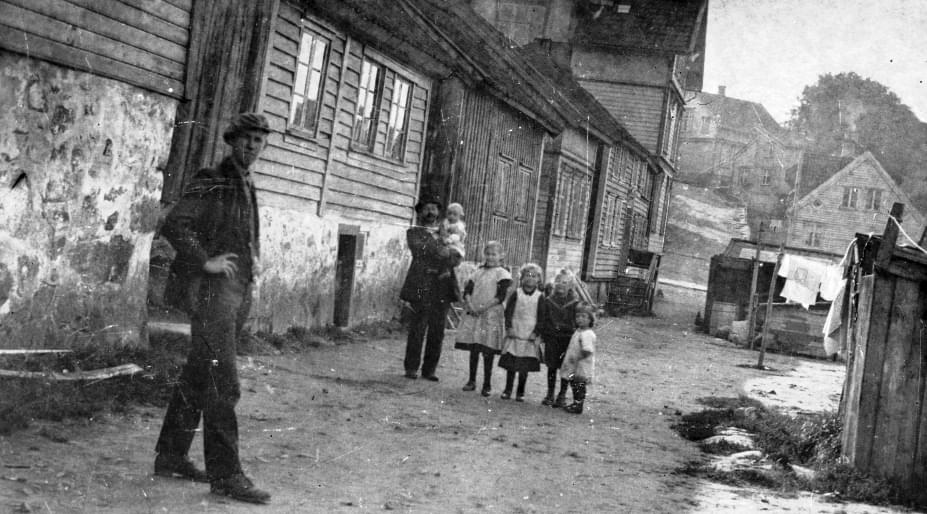

Many poor people had to share accommodation and household areas. In the poor parts of town several families shared small, rickety houses. At Tordenskjolds gate 20, the house that is now located at the open air museum at Kongsgård, 12 people lived on 39 square meters in 1865.

In the cold winter of 1880 a large part of the population of South Norway froze. Individual helpers helped save many lives. Among them was a rich townsman of Kristiansand, the merchant and politician Ludvig Lømsland, who set up and administered soup kitchens for many years. Later, he would also fight for workers’ conditions on a national scale.

At the end of the 19th century, the authorities started to divide up the different groups of poor people into more distinct categories. Hospitals, mental health institutions, elderly care and poorhouses were installed in many places. The work on social insurance and social service started.

The poor people’s home at Halse opened in 1906, and the first municipal old people’s home was established in Mandal in 1918.

Fattigvesenet, the poor relief authority, changed its name to Forsorgsvesenet in 1948, and to Sosialkontoret in 1964. Sosialloven, the Social Security Act, was introduced in the same year.

Today, more than 10% of Agder’s population live in poverty. While poor people of previous ages used to lack heating and food, social isolation is the greatest challenge today. NAV, The Norwegian Labour and Welfare Administration, now handles the responsibilities that the poor relief authority used to have.

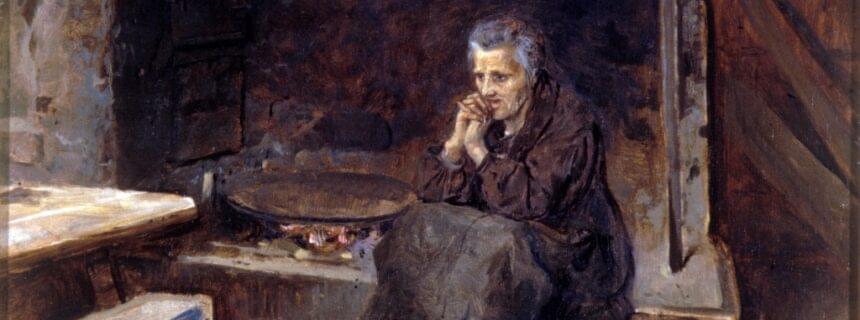

Photo above: Adolph Tidemand, Nød. Belongs to Sørlandets Kunstmuseum. Foto: Stanley Haaland.

Read more: www.vestagdermuseet.no/fattigdom